TRIGGER POINT

If one part of your body is not performing at its optimal level, other areas of the body will compensate. Eventually, these other areas can be compromised as well. Over time, this leads to injury.

Muscles that have Myofascial Trigger Points (MTrPs) have been found to decrease range of motion because of pain. The muscle can fatigue more rapidly as well. But why?

The body will cope with this abnormal level of tension by laying down Myofascial Trigger Points (MTrPs) in the area. A myofascial trigger point was defined by Drs. Travell and Simons as “a hyperirritable spot in skeletal muscle that is associated with a hypersensitive palpable nodule”. It is common for these to form near the neuromuscular junction, where the nerve and muscle meet. In many cases, the surrounding nerves will be affected, and the fascia will thicken, which results in pain and discomfort.

Keep reading to learn more about Myofascial Trigger Points.

WHERE IS THE PAIN COMING FROM?

A 1997 study reported delayed recovery following exercise in 55 patients with MTrPs. In this study, affected muscles showed minimal recovery in seven minutes whereas normal muscles recover 70-90% within one minute. One characteristic of trigger points is that they have a common referral pain pattern. Referred pain is when you feel pain in one area, but the cause is located somewhere else. For this reason it is important to understand more about how the body works before a treatment plan begins.

Furthermore, MTrPs can have significant influence over movement patterns. When pain is present it is common for the human body to alter motion in an effort to avoid pain and move around the restrictive areas. This can lead to movement compensations and muscle imbalances. Muscle imbalances can alter joint range of motion leading to additional myofascial adhesions, restrictive movement, and ultimately, increased risk of injury.

MYOFASCIAL TRIGGER POINTS LEAD TO:

• Increased stiffness

• Decreased range of motion

• Local tenderness

• Referred pain

• Increased sensitivity of the muscle

HOW THE SIX CORE AREAS BREAKDOWN

Previously, we’ve covered six specific areas of the body to better understand overall movement. Here we will revisit the same six spots in order to discover how dysfunction in one area can impact the rest of the body.

Soleus (back of the lower leg)

Quadriceps (front of the upper leg)

Piriformis (hip)

Psoas (abdomen)

Thoracic Spine (upper back)

Pectorals (chest)

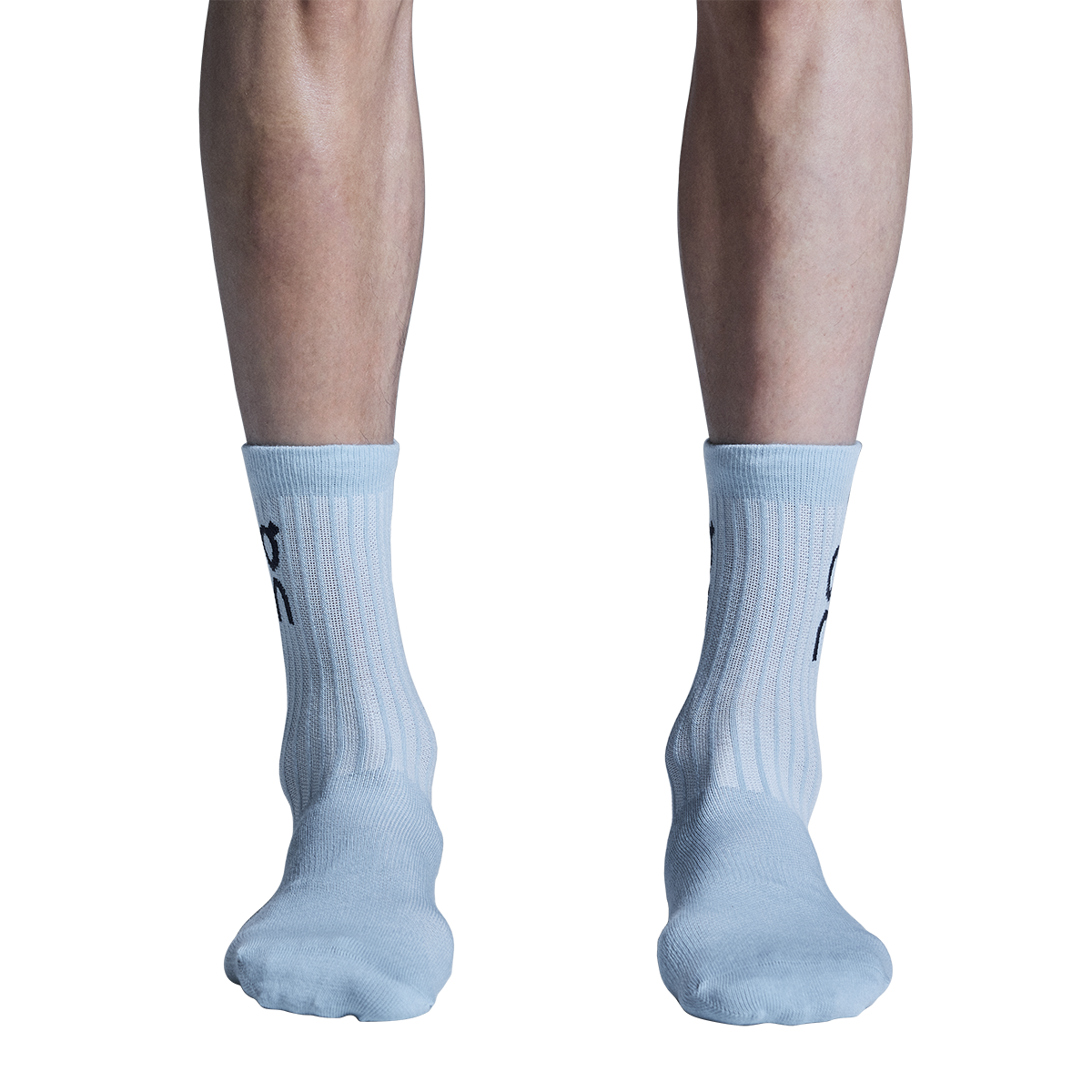

LOWER LEG – SOLEUS

The soleus is one of the most frequently used muscles in the body. It originates just below the knee and inserts itself into the calcaneus via the calcaneal tendon. This muscle is responsible for plantar flexion and acts as an antagonist to the anterior tibias by limiting the amount of dorsiflexion in the foot. As the soleus muscle is overworked, the fascia of the surrounding muscles adhere to this large muscle causing much greater torque on the calcaneus tendon.

UPPER LEG – QUADRICEPS

The quadriceps muscles, which originate in the top of the pelvis, can then cause the pelvis to tilt forward and the buttocks to shift back as they become less pliable. As the pelvis tilts, the upper body shifts forward to counterbalance the weight, often compressing the area surrounding lumbar discs 4 and 5. The more compression there is on the L4-5 area, the more you compromise the neurological feed to the lower extremities. Furthermore, the hamstring muscles and IT band, which counteract the quadriceps muscles, can become stretched beyond their intended functional capacity causing greater inefficiency within the body.

HIP/GLUTE – PIRIFORMIS

The piriformis – a small muscle set deep within the buttocks – also becomes over-strained due to the pelvic tilt. When the piriformis spasms or tightens it can impinge the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve runs directly through the piriformis muscle, and tension in this area can interrupt the neurological feed to the lower extremities of the body. Problems resulting from rigidity, tightness, or weakness in this area can be debilitating for some individuals, resulting in a wide range of issues. Breaking down adhesions and scar tissue along the piriformis is critical for hip mobility.

TORSO – PSOAS

The psoas originates in T-12 & L1-5 and inserts at the lesser trochanter of the femur, making it the only muscle to go from the back to the front of the body. When the psoas is challenged, it can contribute to the upper body leaning in front of the pelvis, which worsens the compression on the L4-5 area. The psoas becomes severely strained as the buttocks tilts back and the shoulders and chest adjust forward in an effort to open up the breathing pathways and to maintain weight distribution through the planes of the body. The psoas primary function is a hip flexor and plays a major role in lifting and rotating the upper leg.

UPPER BODY – THORACIC SPINE

The thoracic spine is an area that is commonly affected by poor posture, poor breathing technique, and if something down the rest of the chain is out of alignment. For example, if the hips can’t move to their full potential then the thoracic spine is often limited in its ability to rotate correctly and transmit force through the upper body. In addition when the shoulders are rounded forward then this area of the upper back gets “stuck” into an overly flexed posture. This flexed position decreases the ability to perform normal functions, such as reaching over your head, without increased risk of injury. Over time, this type of posture will decrease the body’s ability to breathe normally which will lead to more dysfunction through the body. By performing the thoracic spine release the upper back will be able to return to its natural motion and promote rotation, movement of the upper body, and healthy breathing.

UPPER BODY – PECTORALS

The pectoral muscles are also affected in this process due to the body’s natural reaction to rotate the shoulders forward when the torso is positioned slightly in front of the pelvis. This can cause scar tissue build up. By releasing the scar tissue within this region, the shoulders are going to rotate back naturally allowing more oxygen to come into the lungs and allowing the arms to swing freely. This counter action of opening the chest can also allow for better thoracic spine mobility.